I just returned from a pilgrimage.

A pilgrimage, according to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, is a journey undertaken for a religious motive, often linked with a specific place or a sacred event. The pilgrimage, In the Footsteps of the Buddha, was a journey to places significant in Buddha’s life, in the states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, in eastern India.

Shantum Seth, student and follower of Thich Nhat Hanh (or Thay as he is called), the Zen Buddhist Vietnamese monk and teacher, led the pilgrimage. I was introduced to Thay’s teachings in 2008 during a retreat in Delhi and was profoundly affected by the simple message of his teachings on Mindfulness. After the retreat, several people and I joined a Sangha (a group that practices together) in Delhi. I have been active in the practice and Ahimsa Trust, the group directed by Shantum and Gitanjali Seth.

Shantum has been leading the Buddha pilgrimages for almost 33 years. For our pilgrimage, twenty-five of us, men and women, young and old, travelled together. It was a compressed trip, busy and a little tiring. We flew into Varanasi, or the City of Light. After lunch, we had an introductory session, sharing our aspirations for the pilgrimage. Mine was to be present in the areas where the Buddha walked, taught and received enlightenment. We left for the ghats, as they are called, which are steps leading down to the river Ganga or Ganges.

Varanasi is a holy place for Hindus and the aged, sick and dying who come to the city in the belief that a death in the city guarantees nirvana, or no rebirth, and to be cremated. On the steps of two ghats, bodies are cremated. As the sun set, we travelled in a boat up the river, while Shantum told us about the history of the river. We witnessed the cremations from a distance on the water, as the red-orange flames of the wood fires leapt into the air, towards the sky. It was a full moon night, and the funeral pyres were a sharp contrast to the moon.

I first visited Varanasi in 1986, with two friends over my birthday. It was winter, and they knocked on my door at 5 am and said we were going on a boat ride. Not an early riser, protesting, I joined them. It was a magical experience. As the winter morning mists rose, the multiple activities on the ghats began. People doing yoga, washing clothes, worshipping the sun, dipping into the water, dogs chasing each other, priests getting ready to say the morning prayers, singing, chanting, and people just spending time together. Now, 34 years later it did not look much different except for some better maintained buildings, and slightly cleaner.

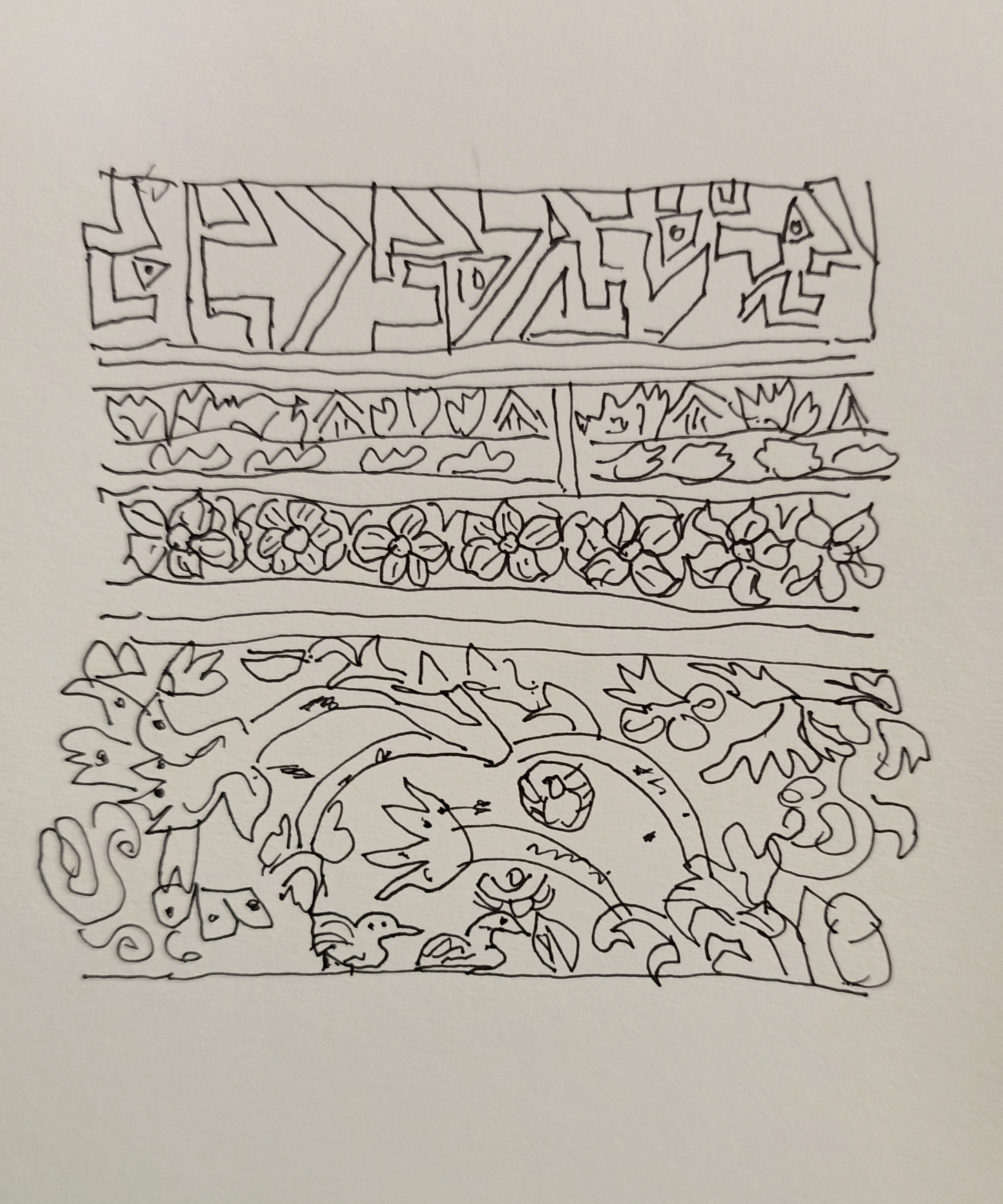

The next morning, we visited the Deer Park in Sarnath, a short distance from Varanasi, where the Buddha gave his first significant sermons on the Middle Way, the Four Noble Truth and the Eightfold Path to his fellow seekers who then became the first monks of his order. A large expanse of a park, it has a grand Dhamekh Stupa with some marvellous carvings of flora and fauna and abstract designs.

The red brick colour of the stupa was a contrast to the greenery of trees and manicured grasses. After a walk around, we sat for a guided meditation and a talk by Shantum about Buddha’s time here. As we left, we walked around the park looking at remains of monasteries, and a part of the famous Ashoka Pillar and the Lion Capital.

Driving through the streets of Sarnath I wondered how the area looked at that time in 528 BCE. At one point, at a stop light, ironically there was a statue of the Buddha with his five monks around him and the red STOP sign.

Our next stop was Bodh Gaya, where Siddharth Gautama become the Buddha as he sat under the Bodhi tree. Driving through the Indian countryside is my favourite part of the journey. Away from the cities and towns, there are open spaces, and at this time of the year after the monsoons, there is paddy and other crops in the fields along with workers, water bodies, and animals. Looking out of the bus window, I could never tire of the kansh grasses, waving in the wind, which are widely seen in India.

As the sun set, we moved towards the Mahabodhi Temple. It was very crowded. Shantum guided us through the various levels of the temple and of course we sat under the famous Bodhi tree which was destroyed several times and is said to be in its fifth generation. Phones are not allowed in the temple, but SLR cameras are. Boys and men in saffron walk around the temple, offering bodhi tree leaves to visitors and then asking for a donation. It is an opportunity for commerce.

The next morning we planned to go back to the Mahabodhi temple and do a meditation under the Bodhi tree. The temple opened at 5 am. We got there at 6 am. It started raining and did not stop for several hours. We took shelter in the security area and Shantum conducted a mediation session. I sat next to the security guard and explained the mediation to him and taught him how to breathe through the abdomen, focusing on his in and out breath. As we left, he thanked me and said he felt very calm and peaceful! Outside the temple, vendors offered beautiful water lilies in pink, purple and fuchsia, picked from local ponds, in recycled plastic water bottles, filled with water. I bought three bunches and kept them in my room.

As with tourist sites, shops lined the area around the temple, selling assorted items, including small and medium-sized Buddhas. They were made from local stone, and I indulged in some of these.

From Bodh Gaya we set out for Rajgir, and on the way stopped at the Dungeshwari temple on the top of a hill. It was at a height, and I took a palanquin. Entering a blackened cave, the statue is of an emaciated Buddha, ribs and veins protruding and a grimace on his face, unlike other Buddha statues. It is said that the Buddha meditated in this case for several years, refraining from food or drink. He got very weak, until a local woman came and offered him food. It was then he decided that this was not the path to enlightenment and instructed his bhikkhus that asceticism was not the way and to go into and be in the world.

The drive to Rajgir through the countryside once again crossed green fields and large rocks and stones and villages. I was happy to see the cow dung patties drying against the walls of houses, which villagers used as fuel. All memories of my childhood as I grew up in a similar area.

In Rajgir, we visited the Bamboo Grove that Buddha was particularly fond of. It was drizzling, and Shantum pointed out the pool of water that the Buddha liked to swim in (I too am a fan of swimming). I rested as the group walked around the park and then as we sat down to listen to Shantum’s talks, the sky turned darker, and it began to pour. Out of nowhere a vendor selling umbrellas appeared, did brisk business. All his umbrellas sold out and I bought one too. It rained steadily for several hours, and eventually we headed back to the hotel. The Bamboo grove was also the site of the first Buddhist monastery.

A favourite place for Buddha was Vulture’s peak, called so after its stone formations that resemble a vulture with its wings spread. At a height of 250 feet, I took another palanquin to the peak. Carried by two young men in a makeshift platform of wooden poles and plastic cane strips, it was safer than it looked. The young men were graduates from local schools and colleges, with no job prospects. During the tourist season, this is what they did. At other times, they worked in the fields or in wage labour jobs. Reaching the peak, it was an incredible site of the mountain peaks all around. We got there at sunset amidst fierce winds and then thunder and lightning. Fortunately, it did not rain till we came all the way down and into the bus. It was dark by then.

There is so much history attached to each site that it is difficult to absorb it all. Our final stop was Nalanda, where the world’s first residential university was established in the fifth century AD and known for its excellence in the fields of Buddhist studies, philosophy, medicine, and astronomy. It attracted scholars from all over the world and was a hub of intellectual activity for centuries. The university was destroyed by invaders in the 12th century. Remains of the university and monasteries are still seen with well-appointed rooms, corridors and greenery. It’s sobering and impressive to think that the reputation of Nalanda’s teachers attracted scholars from places as distant as China, Korea, Japan, Tibet, Mongolia, Turkey, Sri Lanka, and Southeast Asia. These scholars have left records about the ambience, architecture, and learning at this unique university. The most detailed accounts have come from Chinese scholars and the best known of these is Xuan Zang who carried back many hundred scriptures which were later translated into Chinese.

I visited this site with my parents when I was 10 years old and still remember the handful of burnt rice kernels in a bowl in the site museum. In those days, the museum was not so well-preserved. Now it has expanded with the findings from the excavations, it is well-marked and orderly. And as Sanjay, a local guide, whispered to me, “A little too posh.”

Back home, my mind drifts to the sights and sounds of the pilgrimage, the combination of meditation, knowledge, experience and fun with people travelling on the path alongside of me and me alongside of them. The Buddha advocated pilgrimages with the Sangha, or those who practice together, as a way to strengthen the practice.

I returned feeling that my journey on the path to Mindfulness was enhanced by the pilgrimage, as was my practice.

What a lovely yatra, Anita. Much inspired to read it. Rashid

It was good to accompany you on the pilgrimage. Loved your drawings.